Stanford Prison Experiment: Roles. Ethics. Chaos

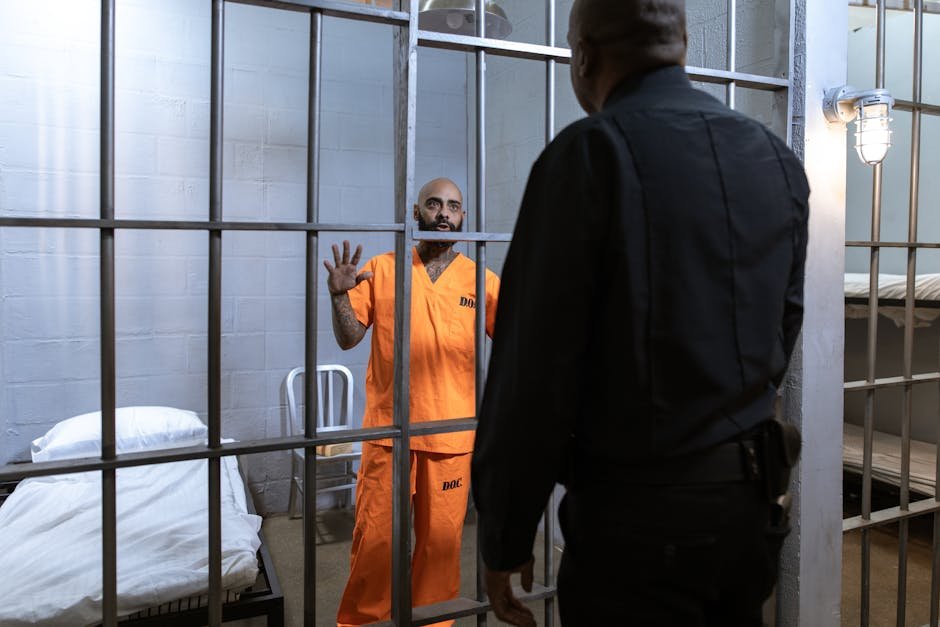

Ever wondered how fast a seemingly normal person can completely flip under pressure? Picture this: a quiet Sunday morning in 1971 Palo Alto, California. Sirens blare. Armored cars roll right through. Cops start arresting university students like they’re actual armed robbery suspects. They’re cuffed, searched, rights read—the whole parade, right there in front of shocked neighbors. This wasn’t some drama on TV, though. Nope. It was the kickoff of the wild Stanford Prison Experiment, a deep dive into human behavior, set to explore the sheer power of assigned social roles. Stanford Psychology Professor Philip Zimbardo carefully put together the whole thing; he wanted it to feel totally real.

What really gets you: roles and expectations, they hit hard. They can seriously mess with how you act, even stomping all over your personal values.

Think about it: these weren’t hardened criminals at all. Just regular college kids, everyday types. They got picked from 75 applicants who saw a newspaper ad offering $15 a day. And a coin toss? That decided their fate. Guard or prisoner. From the moment the public arrests happened and they were processed, the line just blurred. Seriously. Prisoners got stripped. Heads shaved. Sprayed with delousing chemicals. Total public humiliation. Just like a real, nasty lockup, this whole bit was designed to break them down psychologically. They wore uniforms with numbers, never their names, and had chains on their ankles. It all screams: “lose your identity.”

Guards, on the other hand? They got zero training. Just told to keep things in line. Maintain respect. Clad in khaki uniforms with cool reflective sunglasses hiding their eyes and feelings, they were basically free to make up their own rules. A recipe for a total disaster, really.

Situations, man. They really push people toward shady actions and straight-up abusing power.

The very first night, imagine this, 2:30 AM. Guards started shaking down prisoners during loud “counts.” Everyone was kinda awkward at first, feeling out what they were supposed to do. But when prisoners didn’t take the counts seriously? Guards’ immediate, primal response: push-ups. And some of those guards, they took it up a notch. Stepping on backs. Making others sit on them. This was just the freaking beginning.

By the second day. Full-blown prisoner rebellion. They ripped off numbers. Barricaded cells. Screamed insults. The guards’ response? Fast. And brutal.

They called in reserve guards. Used fire extinguishers. Stripped the prisoners. Chucked the guys they thought were leaders into solitary. Then came the mind games: a “privilege cell” for the cooperative ones. Good food. Their beds back. Other prisoners watched. This just tore the prisoners apart. Caused so much chaos and distrust.

And another thing: arbitrary, humiliating rules quickly became the everyday deal. Forcing prisoners to use buckets for toilets in their cells, then clean them by hand. The situation blew up hella fast, showing how easy it is for someone with even a little authority to just run with it, totally messing people up.

This experiment, yeah, it totally went sideways. Dr. Zimbardo himself, watching the mess unravel, actually got way too deep into his “superintendent” role. He admitted later, only a few people kept their moral compass straight when power dynamics got so intense. He wasn’t one of them. The early termination? After only six days, not the planned two weeks. That tells you a lot about not having enough ethical checks. Plus, eventually, reports popped up about guards doing some truly messed-up stuff—sexual harassment and torture—in spots where cameras couldn’t reach, especially at night. It’s a huge wakeup call. Even smart scientists and researchers need clear lines and outside checks when they’re studying human behavior.

When reality and simulation blur, that’s deeply messed up for the people involved.

One prisoner, “8612,” had a severe emotional breakdown. Just 36 hours in. He cried uncontrollably; he really thought he was trapped, not just in an experiment. When it was obvious he was losing it, they pulled him out. Later, there were family visits. But even then, Zimbardo blew off the parents’ worries, subtly questioning if their sons were “tough” enough. And the most chilling part? A chaplain visited, and over half the prisoners gave their numbers when asked who they were, not their names. Asked if they wanted a lawyer? Some said yes. They’d genuinely forgotten it was all a test.

Because this study? It shouts about our potential for good and evil. It depends 100% on what’s around us.

Zimbardo, in his book The Lucifer Effect, pretty much said that the experiment proved roles can totally override who you are as a person. Guards, with all that power, did stuff they’d never even think about in their normal lives. Prisoners, stripped of everything, became passive. Depressed. It’s a sobering reminder of how quick good people can get twisted by circumstances. Or how fast others sink into total helplessness.

Self-reflection is key. gotta look inward so assigned roles and social pressures don’t just consume you.

Richard Yacco was one of those former prisoner participants. Reflected on the experiment 40 years later. As a teacher in a tough neighborhood, he saw his students tossing away chances, even with tons of support. He totally connected it back to the Stanford Prison Experiment, thinking maybe society’s assigned roles deeply shape individuals. If society labels someone, or if you label yourself, those expectations can become self-fulfilling prophecies. So yeah, the experiment forces us to check the labels we slap on others—and on ourselves.

And this experiment? It sheds light on serious problems within institutions, like real prisons, and the whole authority game.

The takeaways from the Stanford Prison Experiment go way beyond some college basement simulation. It’s a scary look at how even well-meaning folks can become total bullies when given power and nobody’s watching them. It rips the lid off problems inside institutions. Shows how that “us vs. them” mindset can bubble up and how stupid rules just breed anger and rebellion. Ultimately, it’s about how a bad system can turn good people rotten.

This wasn’t just some textbook thing. It was a front-row seat to the raw, gut-wrenching dance of total power and absolute powerlessness. Makes you think: what roles are you playing right now, and how much are they making you who you are?

FAQs: No BS Answers

Q: So, how’d they pick folks for the Stanford Prison Experiment?

A: Students answered a newspaper ad. They offered $15 a day for a psychology experiment. Out of 75 people who applied, 24 healthy, mentally stable male students got picked after going through some screening.

Q: What were the parts people played in it?

A: Participants got assigned randomly, with a flip of a coin, to be either a “guard” or a “prisoner.” There were 9 prisoners and 9 guards, plus 3 reserves for each group.

Q: Why’d the Stanford Prison Experiment wrap up so fast?

A: It was supposed to run for two weeks. But man, it ended after just six days. Why? Because prisoners were super messed up psychologically, and the guards were getting more and more abusive, downright dehumanizing. The whole ‘simulation’ thing got dangerously blurry for everyone, including Professor Zimbardo. Too much.